History of Hands-On Teaching Tools

The mannequin and other tools have been the brain-children of Ed Owens over the past 10 years. Ed has a background in biomechanics (MS-ESM from GaTech, 1982) followed by a doctor of chiropractic (Life, 1986) and has worked in chiropractic education and research for 30 years. The original idea for an adjusting mannequin was suggested by Dr. Guy Riekeman when he was president of Palmer College of Chiropractic in the early 2000s. At that time, Ed and Ram Gudavalli worked together in the research center at Palmer College developing tools such as a force-plate embedded in an adjusting bench and hand-held transducers to measure forces of adjustment. They worked on some initial ideas for a mannequin with a force sensor in it, as well as thin flexible pressure sensors over vertebral models suggested by Dr. David Wilder of the University of Iowa and his students.

Fast forward to 2014 when Ed was doing contract work in the research department of Life University, helmed at that time by Guy Riekeman. Again, the suggestion of building an adjusting mannequin came up and Ed took on the task of developing prototypes. He also worked with faculty in the research department to develop a program of research on the forces of adjustment. The first training device was a force plate embedded into a custom-built adjusting bench. It borrowed from the idea of the table used at Palmer College, but had greater flexibility since the force plate was mounted on rails and could be moved up or down the table to measure forces applied to the neck, mid-back or lumbo-pelvic regions. That research program is still in the works today and has resulted in a stream of publications, including some award winners. (Refs 1-5)

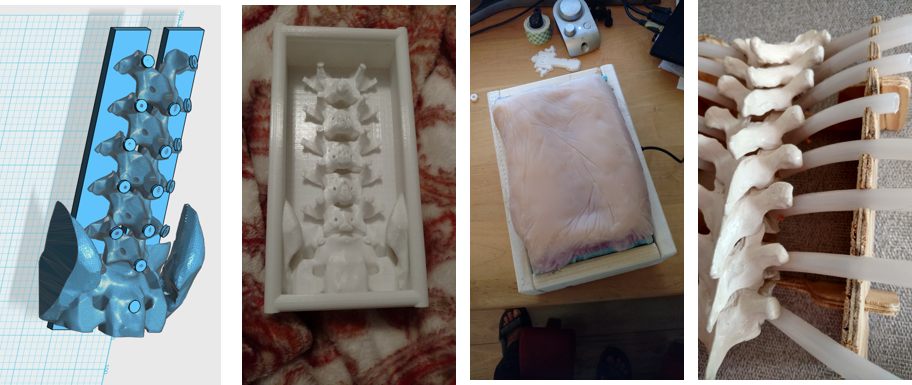

Work continued on mannequin prototypes, with the force-plate table (which is still in use today in Life’s Technique Lab of the Future) as a literal platform for development. Prototypes included the cleverly named “Box-spine,” “RoboSpine,” “Suzy-Q,” and “Blu” (the first silicone encased, full-torso model with moveable lumbar vertebrae and 3 embedded pressure sensors). Prototypes became more lifelike and sophisticated as Ed learned the intricacies of 3-D modeling and printing, silicone molding and casting, electronic sensor system design and microprocessor-based (Arduino) programming and data sampling.

Combining this knowledge with the principles of human spinal anatomy and kinematics and structural engineering from previous education, Ed produced the ever-more cleverly named prototypes “Kevin Bacon,” and “Nicholas Cage.” Kevin 1.0 was the first to incorporate a 3D printed vertebral segment and an array of 16 pressure sensors, 3 on each segment, plus 1 on the pelvis. It looked like a slab of bacon, hence the name. Kevin 2.0 used the sensor array, plus freely moveable lumbar vertebrae, mounted in a box with cable controls to influence joint stiffness. Randy Salvo (a sailing buddy) was brought on board to help with Arduino programming and creation of a display to show the pressure map. Nicholas was the prototype of a thoracic spine, which included tension controls and a rib “cage” made of plastic tubing with a unique telescoping joint.

Liking what they were seeing, Life University commissioned a full-spine mannequin model in early 2019. It began as the combination of the rib and lumbar sections and the development of a new head and neck section, based on the same construction principles with moveable vertebrae and tension controlling elements, and a full-spine sensor array. Needing much better control of the silicone molding process, Ed and Randy brought in a local Savannah artist, Sean Johnsen to produce a beautifully finished product. Sean helped Ed build a mold, based on a store mannequin, and produced the 1st version of a full spine, from head-to-butt mannequin. Randy extended the software model to include a full-spine array of 64 sensors. The project had a drop-dead deadline and was delivered in early June of 2019. Being somewhat androgynous, it was named “Pat” (first name “Pat,” last name “Pending.”)

And then came the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like many institutions, Life University had to suspend in-person classes during the lockdown in early March of 2020. They shifted quickly to online learning. Chiropractic care, though, has a significant hands-on component, incorporating close skin-to-skin contact with patients. They understood that the mannequin would be a great way to simulate hands-on (see how I keep using that term?) teaching without any actual human contact. They contracted with us to produce 20 units of Pat and they wanted them in 7 weeks.

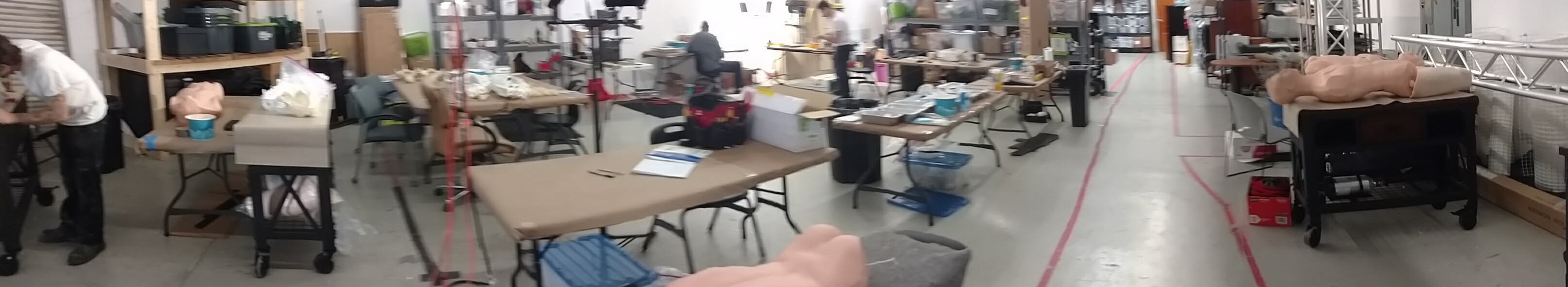

Considering that it took almost 6 months to produce the 1st unit of Pat, 20 units is a daunting task. We had to think big. First, we had to move the operation to Atlanta to take advantage of construction space and extra fabricators at Life University. Second, we enlisted the aid of some special talents. We brought on Andre Freitas whose AFX studios, right across the road from Life University, had been shuttered due to the massive shut-down of film activities in Atlanta. Andre was a silicone artist, like Sean, but on a master-level industrial scale. We had consulted him early when we explored silicone as a lifelike surface for the mannequins and he had great ideas on how to set up a manufactory to handle production of 5 mannequins per week.

We also brought in extra help for building electronics. Aaron Ruscetta was instrumental in streamlining wiring harness construction and later development of a small, monitor-mounted Raspberry Pi computer to handle the display programming very cheaply. Randy pulled a rock-star level move by designing a printed circuit board to mount the Arduino board and the system of multiplexers it took to scan the sensor array. Research staff members Ron Hosek and Rachel Youkey also helped out with wiring and student wrangling.

We used a warehouse bay on the Life campus and employed several students and staff members to machine and assemble parts cast by Andre and Sean into the core of the mannequin. Rachel and Ed affixed the sensors to the bones, and tested the cores thoroughly before delivery to AFX studios for casting and finishing. After the silicone set, we brought the units back to Life for cleanup, leg attachment, electronic installation and final testing. We built 20 units by May 15th, 2020, the so-called “20 in 2020” effort. We wrote up the effort for publication, and the paper won an award at the December 2020 Chiropractic Educators Research Forum Conference. See Ref 6 below.

Since then, Ed has been working to refine the Pat design. He, his daughter Emily, Sean, Randy and Andre produced an additional 5 units for Life University with enhancements to deal with silicone tears that sometimes occur, a better way to seal up the chest cavity and an improved software package.

While to date Life University is the sole owner of all Pat units, much of the work was done while Ed was an outside contractor. Even though Guy Riekeman suggested the idea of an adjusting mannequin, neither he, nor anyone at Life specified any features or functions. The design is completely from Ed’s mind, based on his chiropractic education, and background in biomechanics and biomedical engineering. As sole designer, he applied for a US Patent for the mannequin, which was awarded on Oct 18, 2022 and entitled “Anatomic Chiropractic Training Mannequin with Network of Pressure Sensors.”

Ed formed Hands-On Teaching Tools, LLC in January of 2023 to begin the process of developing the mannequin for other chiropractic programs. Also in the works are ideas for a hand-held sensor pack to measure the contact forces and direction of thrusts applied by students and doctors while adjusting mannequins or humans. Stay tuned for further developments.

References

- Spinal Kinematic Assessment of Chiropractic Side-Posture Adjustments: Development of a Motion Capture System. Weiner MT, Russell BS, Elkins LM, Hosek RS, Owens EF Jr, Kelly G. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2022 May;45(4):298-314. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2022.07.003. Epub 2022 Aug 31. PMID: 36057479

- Mechanical properties of a thoracic spine mannequin with variable stiffness control. Owens EF, Hosek RS, Russell BS. J Chiropr Educ. 2021 Mar 1;35(1):1-7. doi: 10.7899/JCE-19-14. PMID: 32930327 Free PMC article.

- Changes in adjustment force, speed, and direction factors in chiropractic students after 10 weeks undergoing standard technique training. Owens EF Jr, Russell BS, Hosek RS, Sullivan SGB, Dever LL, Mullin L. J Chiropr Educ. 2017 Mar;32(1):3-9. doi: 10.7899/JCE-173. Epub 2017 Aug 2. PMID: 28768115 Free PMC article.

- Thrust Magnitudes, Rates, and 3-Dimensional Directions Delivered in Simulated Lumbar Spine High-Velocity, Low-Amplitude Manipulation. Owens EF Jr, Hosek RS, Mullin L, Dever L, Sullivan SGB, Russell BS. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017 Jul-Aug;40(6):411-419. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.05.002. Epub 2017 Jun 21. PMID: 28645452

- Establishing force and speed training targets for lumbar spine high-velocity, low-amplitude chiropractic adjustments. Owens EF Jr, Hosek RS, Sullivan SG, Russell BS, Mullin LE, Dever LL. J Chiropr Educ. 2016 Mar;30(1):7-13. doi: 10.7899/JCE-15-5. Epub 2015 Nov 24. PMID: 26600272 Free PMC article.

- Development of a mannequin lab for clinical training in a chiropractic program. Owens EF, Dever LL, Hosek RS, Russell BS, Dc SS. J Chiropr Educ. 2022 Oct 1;36(2):147-152. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-10. PMID: 35394042 Free PMC article.